🕹️ 40 Years With the Atari ST: From Zapenu to GitHub

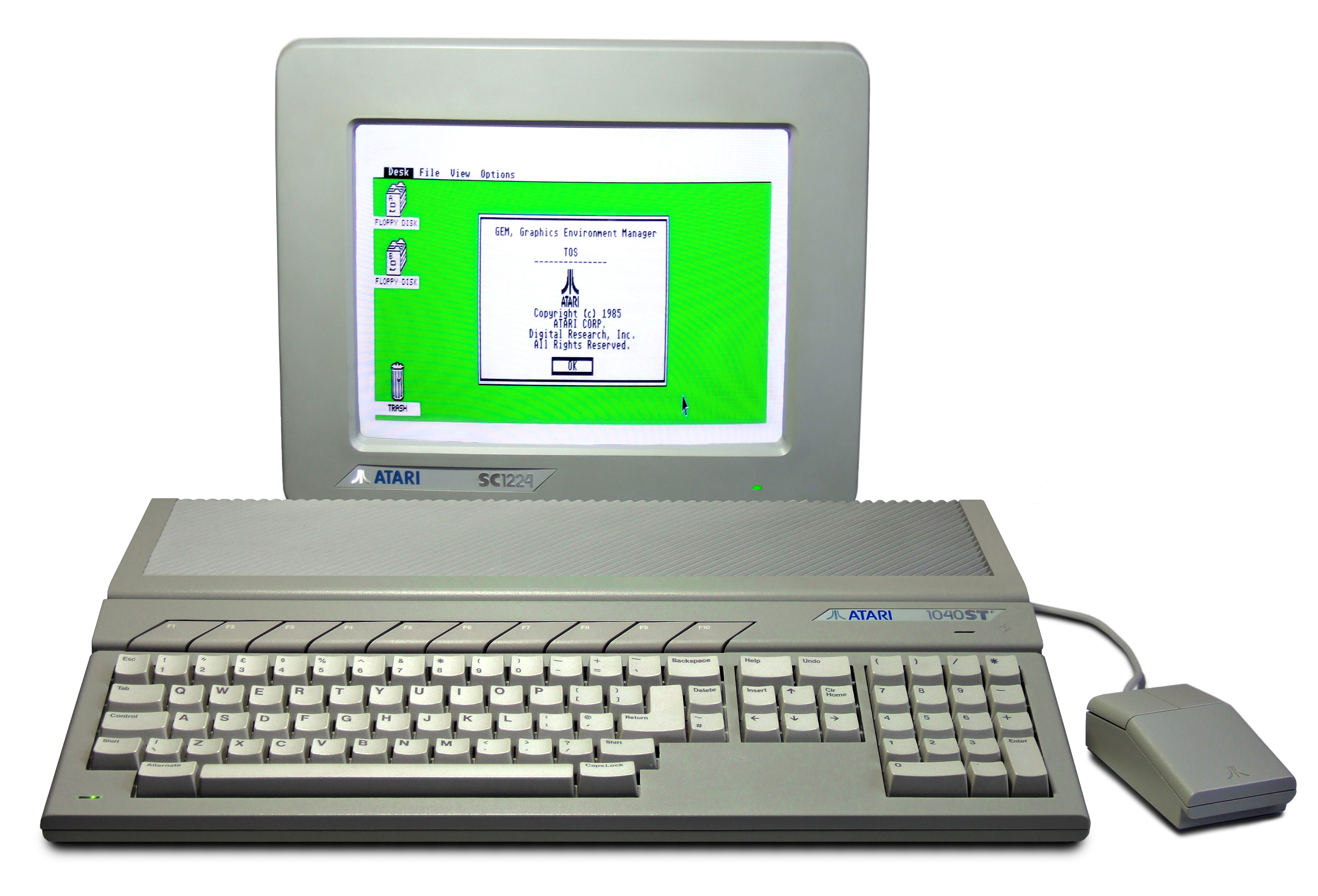

Image by Bilby, licensed under CC BY-SA 3.0 via Wikimedia Commons.

I recently read that the Atari ST turned 40 this year. I remember buying mine at Rosewood Music in Findlay, Ohio, in 1989, using my high school graduation money. I had wanted one ever since 1985, when I first saw it on display at Maumee Valley Computer Center in Defiance, Ohio. That was the year it came out, and it felt like the future. So when I finally got my hands on it — a 16-bit computer with a mouse, a GUI, and built-in MIDI ports — I knew exactly where I was headed. For me, the future was the Atari ST.

Before the ST, I’d been programming in BASIC on my Atari 8-bit. But this was different. This was serious. The ST is where I took off the training wheels and dove into K&R C. No ANSI standard, no IDE, no syntax highlighting. Just me, a blinking cursor, and The C Programming Language in my lap.

I eventually became a registered Atari developer and used Alcyon C — the official C compiler — along with MadMac, a 68000 assembler. This wasn’t just hobbyist hacking anymore. I was writing real software on a real development stack, and getting an early education in systems programming the hard way (and the fun way).

Eventually, I wrote a launcher called Zapenu. It got published in ST Format — not just mentioned, but actually included on the cover disk. That’s how we shared software back then. No App Store. No internet. Just a 3.5" floppy stuck to the front of a magazine, with your code on it. For a college student trying to accomplish real things, that was everything.

Zapenu featured in ST Format Issue 39, cover disk software. Image © ST Format archive.

👑 The ST Was That Good

It’s hard to explain just how far ahead the Atari ST was in the late ’80s or early ’90s unless you were there.

Back then, most people didn’t have a computer at home. Computers were expensive, business-focused, and intimidating. You might have seen a PC at the office or in school — but they were not part of everyday life unless you were a hobbyist or in tech.

The ST helped change that. So did the Amiga, in its own way — though the Mac, while influential, remained out of reach for most people due to its high price. The ST and Amiga proved that powerful, creative machines could be affordable and accessible, not just tools for business or elite institutions.

The ST was affordable, friendly, and powerful — a real 16-bit machine with a graphical desktop (GEM), multitasking desk accessories, and a full C compiler. You could make music, draw pixel art, write papers, play games, or code serious software — all on a single machine.

The Amiga may have had more impressive graphics and sound on paper, but in day-to-day use, the ST held its own — and often felt faster and more responsive. Where the Amiga’s OS felt quirky and inconsistent, the ST’s GEM desktop was straightforward and very usable. It looked and behaved like a real graphical workstation, not just a flashy toy. For writing code, launching apps, or managing files, GEM just worked — and made the whole system feel more polished.

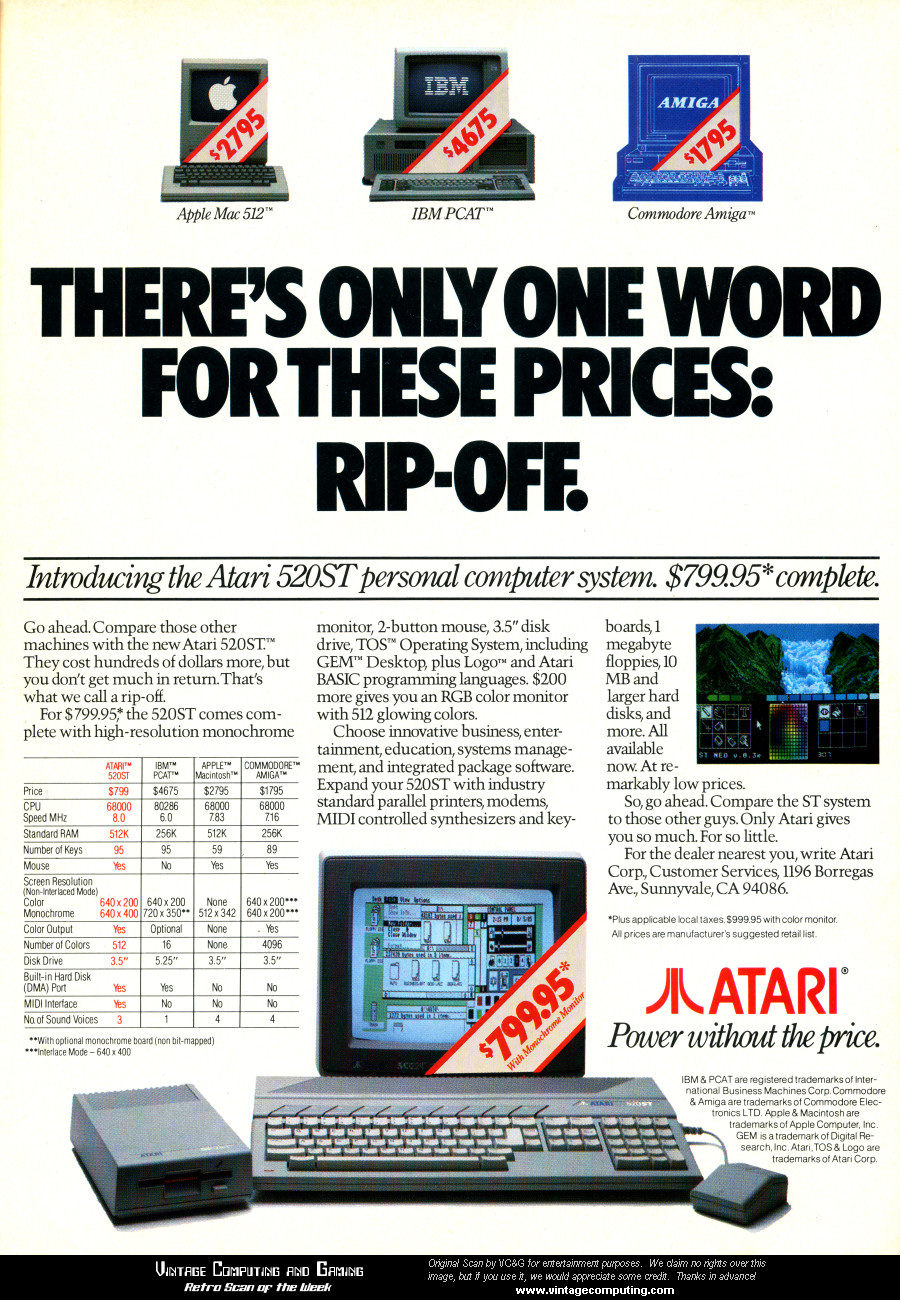

A bold full-page ad from 1985. Atari dared to compare the 520ST’s specs and price directly against Apple, IBM, and Amiga. That “Rip-Off” headline is still burned into my memory.

A bold full-page ad from 1985. Atari dared to compare the 520ST’s specs and price directly against Apple, IBM, and Amiga. That “Rip-Off” headline is still burned into my memory.

Image source: VintageComputing.com (originally from Compute! magazine, Nov 1985).

The ST was also the first time I ever used a WYSIWYG word processor — “what you see is what you get.” Today, people just assume a word processor will show exactly what the printed page will look like — but that was not always the case. Back then, most word processors used markup codes, control characters, or special print preview modes. Seeing your formatting live, as you typed, was not anything I had experienced before. Most word processors back then worked more like text-based consoles — you would type for a while in a terminal-like interface, then trigger a print preview to see what the final document would actually look like. Instead of staring at markup or control codes, I could just type, format, and print exactly what was on the screen.

The built-in MIDI ports made it the music computer overnight. Cubase. Notator. Even pros like Tangerine Dream and Fatboy Slim were using STs long after it was off store shelves — because it just worked.

From a developer’s standpoint, you could write in C, compile directly on the machine, and interact with a real GUI — all without leaving your desk. No cross-compiling. No toolchain setup. Just code and go.

The ST was built fast, on a shoestring, by a team trying to outmaneuver Commodore — the very company Jack Tramiel had just left. That urgency gave it edge. The ST wasn’t designed by committee — it was willed into existence by a man who famously said, “Business is war.” And the ST’s rallying cry captured that spirit: Power without the price.

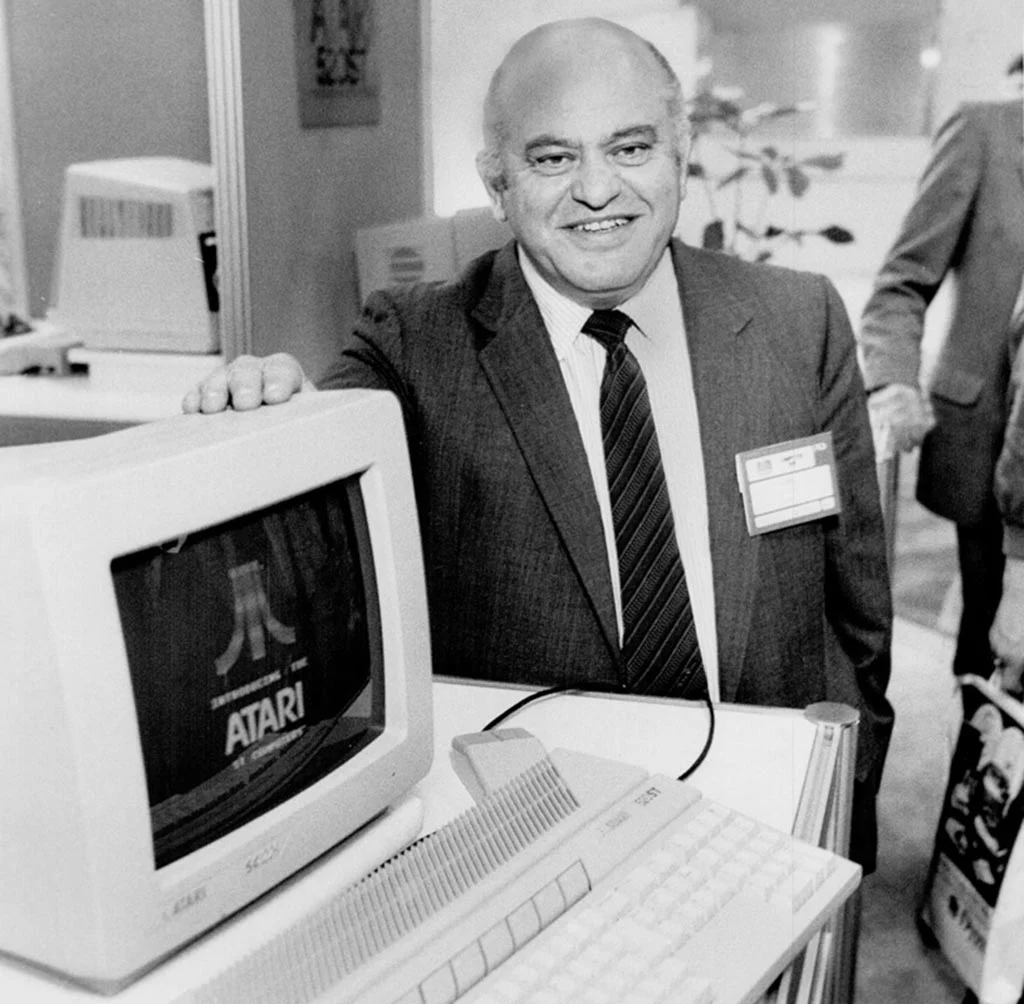

Tramiel doesn’t have the name recognition of Steve Jobs or Bill Gates, but he absolutely should. He survived the Holocaust, came to America, and built not one but two major computer empires — Commodore and Atari — both grounded in his belief that computing power should be affordable and accessible. His legacy isn’t just machines. It’s the idea that the masses deserve technology, not just the elite. And the ST was that philosophy in silicon form.

And when he showed it off — that unmistakable grin on his face — you could tell: the ST made him proud.

Jack Tramiel proudly showing off the Atari ST (Image via Club386.com)

Jack Tramiel proudly showing off the Atari ST (Image via Club386.com)

⚡ Instant-On: The Forgotten Luxury

The Atari ST didn’t just boot fast. It didn’t boot, really — it appeared.

Flip the switch, and in seconds you were at a graphical desktop. No splash screen. No “initializing…” delays. No OS to load from disk. GEM and TOS lived in ROM, so the machine was always ready to go. Even with no disk inserted, you had a working system, complete with GUI, control panel, and file tools.

That kind of responsiveness was normal back then. And then we lost it.

We put up with bloated operating systems, slow hard drives, and boot times measured in minutes. It wasn’t until Mac OS X and Windows XP that things started to turn around — and not until the iPhone that computers truly felt like they’d reached the next level. But even now, most of them don’t feel as personal.

The ST didn’t multitask in the modern sense, but it didn’t need to. It didn’t hide behind layers of abstraction. You flipped the switch, and you were in.

⏳ A Long Time Away

Like a lot of people, I drifted away from the ST in the early ’90s. When I got a 386 and started doing Windows programming, the Atari got boxed up and put on a shelf. It wasn’t a conscious goodbye — just the pull of where the industry was headed.

Windows wasn’t nearly as elegant, but it was where the jobs were. I moved into C++, building real desktop apps for Windows, and later transitioned into Java when the web started taking off. The ST was frozen in amber — a perfect snapshot of when computing felt like discovery, not overhead.

Decades passed. But I never forgot that feeling.

🛠️ Digging It Out of the Past

When I finally pulled my old ST gear out of storage a couple of years ago, I wasn’t sure what I’d find. The hard drive was still there — a huge ACSI unit that hadn’t spun up in nearly 30 years. The hard drive had some rust on the outside but it still worked! I used a Gotek floppy emulator and later an ACSI2SD adapter to carefully pull files off it, one sector at a time.

There were my old source files. My utilities. Even Zapenu. Code I hadn’t seen since I was in college, blinking back at me in a modern text editor.

That moment hit hard. Not just because the data survived — but because I had. I’m still here, still building, still pushing bits around, just like I did in my bedroom all those years ago. I put that code in my GitHub repo, it is available at https://github.com/jbsohn/zapenu.

🎂 40 Years Later

It’s wild to think that the Atari ST is 40 years old. That a machine I bought with my graduation money — the same machine that taught me C, sparked my love of systems programming, and launched a lifetime in tech — is now considered vintage.

But what’s even wilder is how much of it still holds up. Instant-on. Built-in tools. A simple, consistent environment. A sense of control that modern platforms, for all their power, still struggle to replicate.

I’ve written for modern systems — Windows, macOS, iOS, Android. I’ve used Docker, Linux, Swift, Kotlin, and a dozen other buzzwords that would’ve sounded like science fiction in 1985. But nothing has ever quite replaced that feeling of turning on the ST and just building something.

This year, I fired mine back up. Reconnected with the old hardware. Recovered the source. And in doing so, I reconnected with something else: the reason I got into this field in the first place.

Happy 40th, Atari ST. You made a developer out of me.